The texts from the Roman Catholic Lectionary today initiate our observance of Holy Week with the account of Jesus' Passion as portrayed by Luke.

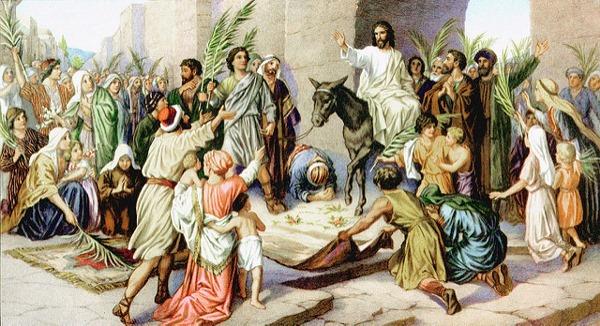

The Gospel Passage for Blessing the palms describes Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem.

* [19:28–21:38] With the royal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, a new section of Luke’s gospel begins, the ministry of Jesus in Jerusalem before his death and resurrection. Luke suggests that this was a lengthy ministry in Jerusalem (Lk 19:47; 20:1; 21:37–38; 22:53) and it is characterized by Jesus’ daily teaching in the temple (Lk 21:37–38). For the story of the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, see also Mt 21:1–11; Mk 11:1–10; Jn 12:12–19 and the notes there.1

The reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah is the humiliation and vindication of the Suffering Servant.

* [50:4–11] The third of the four “servant of the Lord” oracles (cf. note on 42:1–4); in vv. 4–9 the servant speaks; in vv. 10–11 God addresses the people directly. * [50:5] The servant, like a well-trained disciple, does not refuse the divine vocation. * [50:6] He willingly submits to insults and beatings. Tore out my beard: a grave and painful insult.2

Psalm 22 is a plea for deliverance from suffering and hostility.

* [Psalm 22] A lament unusual in structure and in intensity of feeling. The psalmist’s present distress is contrasted with God’s past mercy in Ps 22:2–12. In Ps 22:13–22 enemies surround the psalmist. The last third is an invitation to praise God (Ps 22:23–27), becoming a universal chorus of praise (Ps 22:28–31). The Psalm is important in the New Testament. Its opening words occur on the lips of the crucified Jesus (Mk 15:34; Mt 27:46), and several other verses are quoted, or at least alluded to, in the accounts of Jesus’ passion (Mt 27:35, 43; Jn 19:24).3

The reading from the Letter of Paul to the Phillippians is a plea for unity and humility.

* [2:6–11] Perhaps an early Christian hymn quoted here by Paul. The short rhythmic lines fall into two parts, Phil 2:6–8 where the subject of every verb is Christ, and Phil 2:9–11 where the subject is God. The general pattern is thus of Christ’s humiliation and then exaltation. More precise analyses propose a division into six three-line stanzas (Phil 2:6; 7abc, 7d–8, 9, 10, 11) or into three stanzas (Phil 2:6–7ab, 7cd–8, 9–11). Phrases such as even death on a cross (Phil 2:8c) are considered by some to be additions (by Paul) to the hymn, as are Phil 2:10c, 11c.4

The Passion account in the Gospel of Luke shares the Lord’s Supper to the Burial of Jesus.

* [22:1–23:56a] The passion narrative. Luke is still dependent upon Mark for the composition of the passion narrative but has incorporated much of his own special tradition into the narrative. Among the distinctive sections in Luke are: (1) the tradition of the institution of the Eucharist (Lk 22:15–20); (2) Jesus’ farewell discourse (Lk 22:21–38); (3) the mistreatment and interrogation of Jesus (Lk 22:63–71); (4) Jesus before Herod and his second appearance before Pilate (Lk 23:6–16); (5) words addressed to the women followers on the way to the crucifixion (Lk 23:27–32); (6) words to the penitent thief (Lk 23:39–41); (7) the death of Jesus (Lk 23:46, 47b–49). Luke stresses the innocence of Jesus (Lk 23:4, 14–15, 22) who is the victim of the powers of evil (Lk 22:3, 31, 53) and who goes to his death in fulfillment of his Father’s will (Lk 22:42, 46). Throughout the narrative Luke emphasizes the mercy, compassion, and healing power of Jesus (Lk 22:51; 23:43) who does not go to death lonely and deserted, but is accompanied by others who follow him on the way of the cross (Lk 23:26–31, 49).5

Susan Naatz reflects that our readings today invite us to experience both exuberant joy and profound sorrow.

Several days ago, during the Angelus prayer at the Vatican, Pope Francis said, “Those who wage war forget humanity. They do not start from the people; they do not look at the real life of people but place partisan interests and power before all else. They trust in the diabolical and perverse logic of weapons, which is the furthest from the logic of God…put down your weapons! God is with the peacemakers, not with those who use violence.” [source] The words of Pope Francis will continue to echo throughout this holiest of weeks when we face the violence of the crucifixion and death of Jesus. Holy Week is upon us with its messages of hope and despair; joy and grief—intermingled with the promise of salvation. There is a call here to invite Jesus to become a deeper part of our lives. May he be the lens with which we act, serve, and see. And as the world experiences our peaceful actions of love, compassion, and prayer, perhaps they too will declare: “That is Jesus!”6

Don Schwager quotes “The following of Christ,” by Augustine of Hippo, 354-430 A.D.

"Come, follow Me, says the Lord. Do you love? He has hastened on, He has flown on ahead. Look and see where. O Christian, don't you know where your Lord has gone? I ask you: Don't you wish to follow Him there? Through trials, insults, the cross, and death. Why do you hesitate? Look, the way has been shown you." (excerpt from Sermon 64,5)7

The Word Among Us Meditation on Luke 22:14–23:56 reminds us that today is the beginning of Holy Week. It’s the beginning of our own sacred time. For the next seven days, Jesus will appear before us as the suffering Servant of the Lord. Each day we will hear another story that reveals the depth of his love for us. Each day we will see another facet of what it means that he is the Lamb of God who has come to take away our sins.

The hour has come. Jesus is about to offer himself for you. Don’t miss out on the grace of this sacred time. Try to carve out a few extra minutes for prayer each day. Or spend a little more time with the word of God. Or just gaze at the cross a little longer. Let the love that Jesus has for you fill your heart and heal your soul. “Holy Spirit, let the grace of this Holy Week change my heart.”8

Jack Mahoney SJ, Emeritus Professor of Moral and Social Theology in the University of London, looks at the picture that Luke paints for us of Jesus’s arrest, trial and crucifixion. How can this narrative help us to understand that Jesus ‘loved me and gave himself for me’?

As mentioned previously, Luke’s Gospel was written to commend faith in Jesus to Gentile and Roman readers and it is understandable that it gives considerable attention to the Roman trial of Jesus by Pilate – in contrast with Mark, Matthew and even John – showing that the Roman procurator tried on no fewer than three occasions to resist the Jewish religious establishment and acquit the accused. Jesus’s innocence is highlighted repeatedly by Luke, and the political charges laid against him by the whole assembly before Pilate are obviously contrived, including the charge that he claimed to be a king (23:1-2). We may recall, however, that in Luke the crowds on Palm Sunday did change the psalm to acclaim Jesus as ‘the king who comes in the name of the Lord’, to the political scandal of the Pharisees (19:38-39). Perhaps this gave some credibility to the charge, for it was this allegation that Pilate picked up in asking Jesus if he was the king of the Jews (23:3). Hearing also that Jesus had started his prophetic activities in Galilee, Pilate sent him off to be dealt with by Herod, the ruler of Galilee (3:1), for whom Jesus had little time, referring to him as ‘that fox’ (13:32). In fact, Herod and his thugs could get nothing out of Jesus, and he was returned to Pilate in ridicule (23:6-13). The Roman governor next attempted to release Jesus by declaring him innocent against the popular swell of rejection (23:13-16) and by offering to extend to him the traditional pardon that was given at Passover time to a convicted criminal; but ‘the chief priests, the leaders and the people’ demanded that Pilate release another criminal, called Barabbas, instead, and have Jesus crucified (23:13-21). Yet once more Pilate protested he could find no basis for the sentence of death and he now proposed to have the accused flogged and released, a common Roman procedure of acquittal. Yet again, however, he could not prevail and he ultimately surrendered to popular pressure: he gave his verdict ‘that their demand should be granted . . . and he handed Jesus over as they wished’ (23:22-25).9

Friar Jude Winkler relates the texts to Jesus' humility and His response to violence. The unique features of the treatment of the Romans, Luke as philosopher and physician, and special attention to women are discussed. Friar Jude reminds us of the realized eschatology in the Passion Account of Luke.

The CAC Daily Meditations for Sunday, April 10, 2022 were unavailable at publication time.

Meditation on the Passion today is an opportunity for the Spirit to shape our spiritual growth in Holy Week.

References

No comments:

Post a Comment